Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Posted on | February 12, 2016 | Comments Off on Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Mike Magee

My father was one of the 45,000 military doctors to serve in WW II. He entered active duty after his internship in late 1943. By March, 1944, he found himself in Texas receiving special training in Psychiatry. Six months later he would be awarded a Bronze star for his service as an emergency commander of a neuropsychiatric hospital in a war zone in Southern France. Since America’s entry into the war, the Army had attempted to pre-identify and reject any candidates who might be pre-disposed to becoming psychiatric casualties under fire. Military leaders believed selection had been too liberal in WW I, and that this had resulted in high levels of psychiatric distress on the battlefield. By the time my father entered the European war theater, some 2 million draftees or 12% of those examined had been rejected using the military’s new stricter selection criteria. Of the 5 million rejected on medical grounds, nearly 40% were labelled “neuropsychiatric”.

All of this would have been fine with Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, if it had worked. But in the first major test, America’s invasion of French North Africa in Tunisia, American psychiatric casualties were occurring at double the rate seen in World War I. A startling 34% of all battle casualties were labelled neuropsychiatric. Based on the military criteria and rules validated by the new Army Chief of Psychiatry William Menninger, a psychiatric label on the battlefield earned you a one way ticket home. Marshall had had enough. He abolished the screening, and re-enlisted a majority of the men that had been rejected on neuropsychiatric grounds. A later study found that 82% of these former rejectees performed successfully as soldiers.

With involvement in selection gone, Menninger and his Psychiatric colleagues concentrated on battlefield management of what had been loosely labelled “shell shock”. Since World War I there had been disagreement whether the constellation of symptoms that had appeared in 15% of the soldiers was a physiologic condition or some kind of psychological problem. The symptoms included everything from stuttering and crying to deafness and blindness, from hallucinations and amnesia to chest pain and inability to breath. Fundamentally, these soldiers were out of commission, at least for a period of time.

The approach settled on in WW I involved intervention as early as possible and as close to the point of injury as could safely be accomplished. This meant putting psychiatric support into the field and positioning it close to the action. Affected soldiers were initially treated with rest, sedation and warm food. This was reinforced with optimism, persuasion and suggestion. The condition the soldiers were told was “normal” and not their fault. They would get better. Military medical leaders then believed this first step could successfully put about 65% of the soldiers back on the front within 4 or 5 days. If not, the soldiers were shipped to facilities some 15 miles from the front and treated “more aggressively”. If that didn’t work, they went to base hospitals 50 miles from the action and spent 3 months in recovery. If that failed, then, and only then, would they be shipped home.

Marshall liked this approach, especially the part about not linking the condition to an automatic and immediate ticket home. The experience in Tunisia had shown that the more inexperienced the Medical Corps team was, the quicker casualties would be labeled “neuropsychiatric” and shipped out. At Marshall’s request, Menninger came up with a plan. This largely adopted the WW I approach, reinforced by the use of barbiturates and ether anesthesia if necessary for initial sedation of hysterical soldiers. In the most severe cases, other experimental treatments would be utilized like intravenous sodium pentothal, the “truth serum”, to draw out (and hopefully discard) the troubling traumatic memories of war. The echelon system would provide progressive evacuation of more serious cases and echelon 3 would be reinforced with special neuropsychiatric and convalescent hospitals where possible. All this sounded great, except for one thing. There were not nearly enough psychiatrists to execute the plan. So Menninger came up with the idea to train all medical officers in what he called “forward psychiatry”.

To do this he developed a diagnostic manual – Medical 203 (which after the war would become the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM). This was a structured approach to diagnosis and treatment, including the use of barbiturates, and a series of training films which included professional actors to illustrate what the medical officers might encounter. The fictional major in the film not so subtly reinforced that psychiatric treatment was a fundamental responsibility of all medical officers. The soldiers that were being treated were not abnormal people in normal time, but rather normal people trapped in an abnormal time. Every man has his breaking point was the message. These men were not “shell shocked”, they were suffering “battle fatigue”.

My father, in March, 1944 received the new training with other medical officers. He viewed the War Department Official training Film 1197. It had been produced on October 20, 1943 and titled: Early Recognition and Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Conditions In The Combat Zone.

The film began with a static slide that read:

““Any medical officer may be called upon to treat neuropsychiatric casualties. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists, the burden of early recognition and treatment of these casualties will fall on medical officers without special training. The attention of all medical officers , therefore, is invited to their responsibility for the mental as well as the physical health of military personnel.”

Early in the film, Menninger surfaced all the major objections doctors like my father might have by having the “Medical Officers” in the film raise questions with the “Major”. After a brief opening film segment showing an hysterical fictional patient with battlefield exhaustion, the major invites comments. Officers objections: 1) “I don’t see what else the officer (in the film) could have done. There doesn’t seem much point in keeping a patient like that on the battlefield”. 2) “Major, we’re going to be busy out there with patients who are really shot up and we won’t have time to monkey around with guys like that.” 3) “Major, I’m a surgeon. Looks to me like this is a job for psychiatrists.” 4) “That soldier must have been a misfit from the start to break down like that.”

The major’s response sets the record straight in pretty clear terms: “Gentlemen, you are not requested to treat these patients. You are directed to do so. May I acquaint you with a few statistics from recent campaigns. The size of the problem will startle you. These figures from Italy seem to indicate that 20% of all the non-fatal battle casualties were not wounded. They were suffering from neurosis. In Sicily the overall figure for the entire campaign was 14.9%. When you add up the easy and the hard days of the Tunisian campaign, you will find that 16% of all the non-fatal casualties were suffering from neurosis. In prolonged engagements where the going is really tough, we find that 30% to 50% of all men coming under your care in the divisional area are suffering from combat exhaustion…That means that 1 out of 3, or even 1 out of 2 soldiers coming under medical canvas does not have one drop of blood on him…..You are the members of the Medical Department and to you are entrusted the care of all of the sick. There are no specialists on the battlefield. If you say you are a surgeon and can only handle the surgically impaired, you have failed in your mission. Out in the mud, you’ve got to be a medical soldier and meet all comers.”

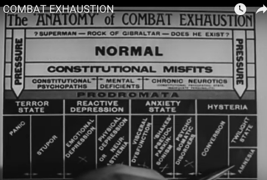

Now that he had my father’s and the others attention, they got down to business. A diagnostic tree with 4 conditions including hysteria, anxiety state, reactive depression, and terror state. Cutting across these four categories are the soldiers themselves who vary from being “Superman – Rock of Gibraltar” to “NORMAL” to “Constitutional Misfits.” The message is, “You will be dealing with all comers, and they will vary widely, but they all need your help.”

Then seamlessly, the major moves on: “…let us review some of the drugs available to us in narcosis therapy and chemical hypnosis available in your #2 Chest..”

1) Sodium Amytal: 9 to 12 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep) …wake, feed, bathroom…re-treat for total 24 hours. Also available IV (5 to 8 cc) (EI Lilly)

2) Nembutol: 4.5 to 6 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep)…in combat zones, massive doses are needed in treatment.

3) Phenobarbital: 4.5 to 6 grains (10 to 12 hours sleep)

4) Sodium bromide: dose and effect highly variable. Can be toxic. Used only if nothing else is available.

5) Pentothal IV: Short acting “truth serum” to surface suppressed memories.

6) Ether: Can be used to get unruly patients under control.

And in conclusion the Major delivers a clear instruction that would be actively followed by doctors in war zones, and become embedded in the practice of medicine for the next half century, “You have the facility of sedation and reassurance. Use them.”

At the end of the war, the doctors returned home with a distinct bias toward specialization and pharmacologic intervention – name it, treat it, cure it. Medical 203 morphed into DSM. By 1970, with the Medical-Industrial Complex now near fully funded by government research dollars, one in seven American adults, bruised by the Cold War, were on tranquilizers.

Tags: battlefield exhaustion > DSM > medical 203 > Military Medicien > overuse of psychiatric medicines > selective service WW II > shell shock > william menninger > WW II