Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 3. The Prescription.

Posted on | September 10, 2019 | Comments Off on Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 3. The Prescription.

Mike Magee

William Radam’s “Microbe Killer”, and other variations of mistreatment, with or without healer negligence, were mainly what instigated two hundred and fifty physician delegates from 28 states to coalesce at the founding meeting of the American Medical Association in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on May 7, 1847. The meeting had been triggered by a motion from Nathan S. Davis, a young New York physician and member of the New York Medical Association in 1845, calling for a national convention. At that 1847 meeting, the delegates approved the establishment of the organization, elected Nathaniel Chapman its’ first president, approved a Code of Ethics, established nationwide standards for preliminary education and the degree of MD – and then called it a day.

But then, over the next 24 months, this young organization, according to its official history, “analyzed quack remedies and nostrums to enlighten the public in regard to the nature and danger of such remedies”; “recommended that the value of anesthetic agents in medicine, surgery and obstetrics be determined”; “noted the dangers of universal traffic in secret remedies and patent medicines”; and “recommended that state governments register births, marriage and deaths”.

Of course they also painted their competitors, homeopathic physicians and osteopathic physicians, with a broad negative stroke. Over the next half century, homeopathic physicians would disappear and Osteopathic Medicine would be repeatedly labeled as a “cult”. It would take over 100 years for the AMA to grudgingly agree to the equivalency of an M.D. and a D.O.

But for the young immigrant cousins, Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhardt, who arrived in Brooklyn in 1849, the timing couldn’t have been better. They intended to produce chemicals and medicinals that were safe and effective. And they saw these new physicians, certified and focused on routing out their “quack” competitors as an asset, a “learned intermediary” that would deliver their product reliably and with implied professional endorsement to patients far and wide. What could be better?

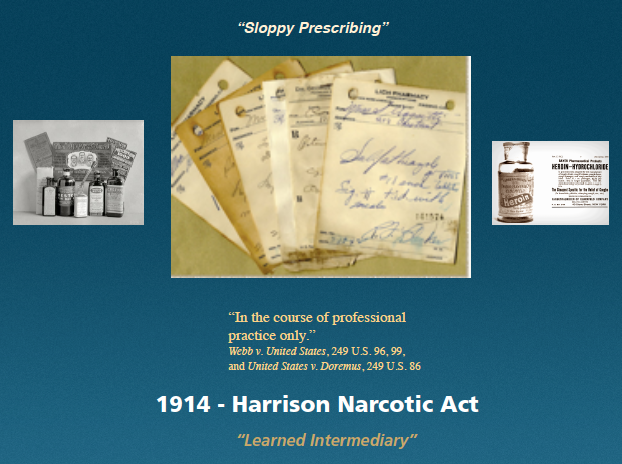

The sales vehicle that would close the deal, a prescription, became commonplace after 1914, when the Harrison Narcotic Act “required prescriptions for products exceeding the allowable limit of narcotics and mandates increased record-keeping for physicians and pharmacists who dispense narcotics.”

That single stroke of the pen had enormous ramifications that we are arguably still negotiating today. The boundaries it established included: separation of duties for physicians and pharmacists; separation of disciplines of pharmacy and pharmaceutical manufacturer; legal cover from some liability for pharmaceutical manufacturers, who once their drug is “approved” by the FDA, hand it – and its liability – over to the physician “learned intermediary” to prescribe; separation of product that exists behind the counter and requires a prescription, from product that is “over the counter”; and separation of product that is still under patent protection from “generic” product which is not protected.

Of course the full ramifications of the 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act were yet to play out. Most of the issues above were only addressed by case law in the later part of the 20th century. Some remain evolutionary and unresolved today. What was obvious at the time was that the AMA was “in charge” of Medicine in America, at the top of the heap. They were aggressive and organized. Through the Flexner report, they would soon radically shrink medical schools and hospitals, forcing the survivors to tow a “quality line” that they alone had defined. They would jealously protect the “right to prescribe”, and in so doing hold competing practitioners, and increasingly educated patients, at bay for most of the next 100 years. They would turn a blind eye to “sloppy prescribing” and willingly accept the ad dollars and physician masterfile data revenue from pharmaceutical companies that would ignite a deadly opioid epidemic a century later.

And they would do all this with the very active support of Charles Pfizer, Charles Erhardt, and their pharmaceutical colleagues, who would grow very, very rich in the process.