PBM’s – Their Origins and Parentage.

Posted on | April 17, 2022 | Comments Off on PBM’s – Their Origins and Parentage.

With the controversy swirling over insulin pricing, and sticker shock for seniors meeting deductibles on their Medicare Part D choices, it’s useful to shine a light on PBM’s – their origins and parentage. They would, of course, prefer to remain in the shadows, managing a vast array of legal kickbacks with others within the Medical-Industrial Complex.

And yet they and their middlemen hold 6 of the top 25 spots in the Fortune 500. Here’s a starter course, excerpted from “CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical Industrial Complex” where the full story resides.

“When PBMs began, insurers and employers believed that this new entity might contribute to cost control by efficiently processing prescriptions, maintaining approved drug formularies, and holding down prices. But they soon realized that ownership of a PBM by a drug-maker, insurer, or a retail pharmacy giant allowed the owner to coordinate pricing decisions, see competitors’ pricing information, and favor some drugs over others in return for kickback payments, even if the consumer unknowingly was forced to pay more.

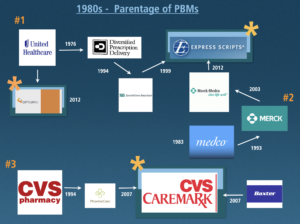

There are now about thirty different PBMs. But three major companies control 78 percent of the PBM market and service 180 million Americans. These opportunistic middlemen emerged from three different Medical Industrial Complex (MIC) industry sectors: a physician managed care group, a pharmacy corporation, and a pharmaceutical manufacturing company.

The first one, Diversified Prescription Delivery, was developed in 1988 by UnitedHealthcare, the insurance company that grew out of a physician-run managed care medical group called Charter Med, incorporated in 1974. They were the first to recognize that new information technology would revolutionize the health care industry. Where the WHO owned the ICD-9 diagnosis billing code databases, and the AMA owned the CPT procedure billing code databases, UnitedHealthcare ambitions were far more expansive–to control and mine patient databases themselves. From this perch, they were the first to develop pharmacy drug formularies, hospital admission pre-certification requirements, physician office software that predated electronic medical records, and tight controls on utilization beyond those of other HMO’s at the time.

The realization that data now was king spread rapidly. A second PBM, PharmaCare, appeared as an offering from CVS in 1994, and in 2007 was renamed CVS-Caremark. The third dominant PBM, mail order giant Express Scripts, has a complex parentage. It was formed from the purchase of a SmithKline Beecham’s PBM in 1999 and the addition of Merck-Medco in 2012. Five years later, in 2017, Express Scripts reported revenue of over $100 billion compared with Pfizer’s $52 billion of revenue that year.

Their sphere of influence and market power derives from the fact that approximately 4.5 billion prescriptions are filled in the US each year. Americans’ appetite for legal drugs is close to insatiable. Just under 50 percent of US residents have filled a prescription in the last month, and 10 percent of our population currently takes five or more prescription medications.

Approximately $50 billion is expended each year in the manufacturing of these drugs, which move primarily through three giant wholesale distributors in the US—AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson—on their way to the retail pharmacy. Their combined revenue in 2015 was $378 billion for distributing the drugs to 60,000 pharmacy outlets, 63 percent of which are part of large retail chains. By 2017, their combined revenue reached $481 billion.

PBMs are now the Grand Central Station of the legal trade of drugs and the primary processors of patient and insurance enrollee data. They negotiate the deals for each and every drug with pharmaceutical companies, the placement of those drugs on insurers’ and employers’ tiered insurer formulary drug lists, and the integration and management of utilization and cost strategies with pharmacies, insurers, and hospitals nationwide. Their cutouts and givebacks to both the drug and insurance industries, and negotiations with hospital systems, share the profits and are nontransparent. Nearly everyone is in on the deal—except the patient.”

Tags: cvs > legal drug trade > medical-industrial complex > merck medco > Optum > PBM