Structural Racism Within The Medicaid Program – Still Present a Half-Century Later.

Posted on | September 9, 2020 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

If you would like to visit the meeting place of America’s two great contemporary pandemics –COVID-19 and structural racism – you need only walk down the historic Medicaid path and enter the dangling door of its weakest health care link, the Nursing Home.

The current pandemic is disproportionately killing and maiming Black Americans. This should come as no surprise to Medical Historians familiar with our Medicaid program. Prejudice and bias were baked in well before the signing of Medicaid and Medicare on July 30, 1965.

President Kennedy’s efforting on behalf of health coverage expansion met stiff resistance from the American Medical Association and Southern states in 1960. Part of their strategic pushback was the endorsement of a state-run and voluntary offering for the poor and disadvantaged called Kerr-Mills. Predictably, Southern states feigned support, and enrollment was largely non-existent. Only 3.3% of participants nationwide came from the 10-state Deep South “Black Belt.”

Based on this experience, when President Johnson resurrected health care as a “martyr’s cause” after the Kennedy assassination, he carefully built into Medicaid “comprehensive care and services to substantially all individuals who meet the plan’s eligibility standards” by 1977. But by 1972, after seven years of skirmishes, the provision disappeared.

Ever the political pragmatist, President Johnson had focused instead on Medicare and hospital compliance, rather than Medicaid and Nursing Homes. And that alone was a pitched battle at the time.

In the 1960s, hospitals throughout the South still maintained segregated restrooms and segregated floors and wards designed to separate black and white populations. The passage of the Civil Rights Act in July 1964 had sent a clear warning: Title VI of the bill stated, “No person in the United States shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, denied benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any program receiving federal assistance.”

Johnson deployed 1,000 federal inspectors across the country to ensure that the letter of the law was being implemented. Even with this, 10 months after Medicare had been signed into law, and a month or two before the launch date, half the hospitals inspected in 12 Southern states were still noncompliant. So he leaned on Vice President Humphrey to head south and communicate directly with every mayor in the noncompliant Southern cities and simply, one way or another, get the job done.

By May 23, 1966, all hospitals were compliant except in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. By July, they were clearly heading in the right direction, though 320 hospitals had not yet completed the conversions. All would soon comply.

Medicaid has always disproportionately served as a backstop for Black Americans. They are more likely to be financially eligible, and more likely to spend their final years in Nursing Homes funded by Medicaid dollars. They are also likely to die younger than white counterparts, have twice the rate of heart disease, high blood pressure and stroke. For younger Black women, lack of access to maternity care and mental health services places them at high risk. Their children are 500% more likely to die of asthma than white children.

As for Medicaid, a half-century later, we’re still fighting the same discriminatory battle, and largely in the very same states.

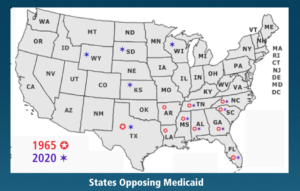

Southern states, led by Republican governors, have led the way in a decade long battle to collapse the Affordable Care Act, and most notably the 90% federally funded expansion of Medicaid services and eligibility which the Supreme Court deemed voluntary in a landmark 2012 decision. Until 2017, eighteen states stubbornly held ranks. But in the past three years six states (Idaho, Utah, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Maine and Missouri) have fallen in line after voter propositions passed in their states.

That leaves some 2 million vulnerable citizens without coverage that is readily available. Polls in those states show that 2/3rds of their citizens favor Medicaid expansion in opposition to their own governors – and that was before the pandemic. Even in red counties of red states, 1/3 of Republicans are polling in favor of Medicaid expansion.

When COVID-19 hit, Nursing Homes were at the epicenter. The major Southern states resisting enrollment in Kerr-Mills in 1965 were Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. Today, eight of the twelve states resisting Medicaid are the same. These 12 states account for 92% of adults eligible for but not covered by expanded coverage. As such, they are last in line for COVID-19 testing, PPE, and vaccines when they arrive.

As a recent Health Affairs article concluded: “Addressing these ills through policy is not the only step needed to end racism in our country, but it is a necessary—and long overdue—step.”

Comments

2 Responses to “Structural Racism Within The Medicaid Program – Still Present a Half-Century Later.”

September 10th, 2020 @ 10:00 am

The facts of this discrimination have been exposed countless times in the last 50 years but arguments based upon logic, common decency and respect for others have failed to dislodge the practices of overt and covert discrimination. It appears almost to be in the genes of some people. So the question becomes what is left to do to eradicate this cultural cancer?

September 10th, 2020 @ 10:08 am

Thanks for this, Larry. I’m not sure we’ll ever know what makes a society move and a culture evolve. But crises clearly play a role in achieving a “tipping point.” On Nov. 3rd, we will witness whether America is ready to confront our troubled past. Best, Mike