Death by Environment: The Boomerang Effect of Poor Environmental Policy

Posted on | March 16, 2016 | 1 Comment

Source:IndexMundi

Mike Magee

The WHO released a report this week that suggested that nearly 1/4 of all human mortality (22.4%) in 2012 was secondary to unhealthy environments.

We have known for some time that planetary health has an important impact on human health. It effects not only the quantity of years an average planetary citizen lives, but also the quality of those years. This, in turn, can be a major determinant of human productivity and ingenuity, and an important factor in our efforts to maintain safe, stable and secure human societies.

When examining global human resources, social scientists often begin with the number of births and the number of deaths per 1000 in various geographic localities around the world. “Refreshing” the human population is essential to revitalizing the human workforce, and in maintaining the most productive demographic age balance. The reality is that we rely on new healthy workers to support the growing needs of aging populations who consume more health and social resources as they grow older.

The WHO has added a new wrinkle to their most recent studies by attempting to quantify the human mortality costs of an unhealthy environment. Environmental degradation increases the chronic burden of cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, as well as all types of cancer. Weak environmental laws and infrastructure also are responsible for deadly poisoning by toxins and outbreaks of infectious diseases. Finally, extreme environmental degradation can be associate with collapse of adequate food and water support, mass migration and warfare and anarchy.

What do we know about the 56 million who died worldwide in 2012? Let’s break it down. On average that year, just under 8 (7.99) people died per 1000 citizens during the course of 2012. That figure remained roughly the same in the 2014 readings. The highest death rates occured in South Africa (17.49/1000) and in the Ukraine (15.72), and the lowest occurred in Qatar (1.53/1000) and United Arab Emirates (1.99/1000). The U.S. came in at 8.15/1000, just below Switzerland (8.1/1000), but higher than Canada(8.31/1000) and the U.K.(9.34/1000), Japan (9.38/1000) and Sweden (9.45/1000). But before we engage in too much self-congratulation, realize that higher mortality rates often reflect aging demographics rather than generalized poor health.

Going back to the UN report, here are a few interesting findings:

1. 12.6 million of the 56.4 million deaths worldwide were related to “living in an unhealthy environment”.

2. “Environmental risk factors, such as air, water and soil pollution, chemical exposures, climate change, and ultraviolet radiation, reportedly contribute to more than 100 diseases and injuries”, according to the report.

3. 2/3 of the “environmental deaths” (8.2 million) were the result of non-communicable disease such as stroke, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer. In this arena, indoor and outdoor pollution, including the use of fossil fuels for domestic cooking, heating, and lighting, and secondary cigarette smoke, were the major offenders.

4. “Regionally, the report finds, low- and middle-income countries in the WHO South-East Asia and Western Pacific Regions had the largest environment-related disease burden in 2012, with a total of 7.3 million deaths.”

Children under five and adults age 50 to 75 were the most likely to suffer an “environmental death”. Approximately 1.7 million deaths in children and 4.9 million in adults were deemed preventable were appropriate health policies to be implemented.

What policies? The WHO report lays out a range of actions. Here are a few of their suggestions:

“Using clean technologies and fuels for domestic cooking, heating and lighting would reduce acute respiratory infections, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases and burns.”

“Increasing access to safe water and adequate sanitation and promoting hand washing would further reduce diarrhoeal diseases.”

“Tobacco smoke-free legislation reduces exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, and thereby also reduces cardiovascular diseases and respiratory infections.”

“Improving urban transit and urban planning, and building energy-efficient housing would reduce air pollution-related diseases and promote safe physical activity.”

Tags: cigarette smoke > environmental deaths > environmental health > fossil fuels > global mortality rates > planetary health > pollution > second hand smoke > WHO

End-of-Life Care Options

Posted on | March 9, 2016 | 1 Comment

Sophia Bernazzani

When your loved one is given months or even weeks to live, it can result in a tidal wave of emotions for you and the rest of the family. Questions such as “Where will he stay?” or “How will we keep her comfortable?” immediately spring to mind. End-of-life care refers to the various types of services available to someone who is approaching death. Nursing@Simmons has created a guide that explains the five primary options for receiving end-of-life care. Below we explore the basics of each

1.Home

People who choose to live out their final days at home typically have family support and good financial resources combined with a desire for independence. The amount of external support required depends on the person’s condition and whether or not a nearby family member is available and willing to help out. Types of services needed by a homebound patient may range from help with daily activities and medical needs to transportation. In addition to a close family member, he or she may enlist the help of:

- Home health agencies

- Professional caregivers

- Community-based hospice or palliative care programs

Payment sources: Medicare/Medicaid, private and/or long-term care insurance, Veterans Administration (VA), and patient/family resources

2. Hospice

Hospice is generally an option for those with a life expectancy of six months or less. Hospice care focuses on keeping a person comfortable rather than on finding a cure. It can be administered at home, in a hospital, in a long-term care facility, or at a freestanding hospice house. Hospice facilities cannot refuse care based on a patient’s inability to pay.

Payment sources: Medicare/Medicaid hospice benefit, private insurance, and patient/family resources

3. Hospital Inpatient Care/General Inpatient Hospice (GIP)

These options are usually for very ill individuals who require constant medical monitoring. They may be cared for on a general nursing floor of a hospital or in an intensive care unit (ICU). In these settings, a patient often has access to a palliative care team, which involves providers working together to tend to his or her physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

Payment sources: Hospital inpatient costs to Medicare/Medicaid have increased significantly over the past five years, but out-of-pocket costs to patients/families remain minimal and unchanged.

4. Long-Term Care Facility

Long-term care settings include assisted living facilities, which cater to semi-independent people who need assistance with some daily living and nursing tasks, as well as skilled nursing facilities, which provide comprehensive care for more complex needs.

Payment sources: Long-term care insurance and Medicaid (covers room and board if eligible)

5. Palliative Care

This type of end-of-life care is for seriously ill people who require ongoing pain and symptom management. Palliative care can be provided in any setting and can maximize quality of life for patients and families during the final days. Palliative care experts are qualified to assist with a variety of end-of-life issues, including goals for care and advance directives. Models of care include:

- Hospital-based consult teams

- Inpatient palliative care units

- Community-based palliative care programs

Palliative care has been shown to reduce costs for both patients and health care organizations. People who receive this type of care earlier in their hospitalization are less likely to be in the ICU. Plus, studies actually show lower inpatient costs with palliative care.

Easing a Difficult Decision

Choosing the location for end-of-life care is a tough decision that must be made with input from the patient, family, and primary care provider. Carefully evaluating the full range of options available — as well as their associated costs — can help you ensure affordable care, greater comfort for your loved one, and peace of mind all around.

Tags: aging > home care > hospice > long term care options > Nursing @ Simmons

Remembering My Parents and the Reagan’s

Posted on | March 7, 2016 | 3 Comments

Mike Magee

The words on the May 7, 1992, University of Pennsylvania report, signed by psychiatrist Gary Gottlieb, could hardly have been more definitive. They read, “Dr. Magee’s pattern of results suggests moderate to severe diffuse global impairment with functions mediated by the temporal and frontal lobes being affected to a greater degree. His performance on measures of higher cortical functioning appear to be consistent with a primary degenerative disorder such as Senile Dementia of Alzheimer’s Type (SDAT).”

The verdict was not a surprise, and still it was shocking to see it there on the page in black and white. My mother had quietly hidden my father’s growing disorientation and memory difficulties for quite some time. I had first noticed some mild changes at a celebration of my father’s 75th birthday in Florida three years earlier. In the past year, he had become more and more forgetful, and had gotten lost several times while driving. Lately he was intermittently confused, and repeating events and questions over and over. He was more easily frustrated, even dazed at times. My mother knew something was very wrong, and knew she finally needed help.

On the West Coast, another woman of similar age and disposition was noticing similar changes in her own husband. He too had been a remarkably capable individual, with a large following of devotees; a man quick to smile and converse with strangers; a man capable of inspiring hope and confidence with his social skills and aptitude; a man who also enjoyed being front and center, “on the stage”. His name was Ronald Reagan.

The two couples had never met each other, yet their similarities were striking. For both, their marriage, and commitment to each other was paramount. Both marriages would last 52 years, interrupted only by the death of a spouse – in one case the wife, in the other the husband. Both wives would be the primary caregivers and protectors of their husbands, only grudgingly accepting support and help, remaining the primary and final arbiter, “until death do us part”.

In describing their marriage, one of the men wrote, “I more than love you, I’m not whole without you. You are life itself to me. When you are gone I’m waiting for you to return so I can start living again.” And his wife later explained, “If either of us ever left the room, we both felt lonely. People don’t always believe this, but it’s true. Filling the loneliness, completing each other – that’s what it still meant to us to be husband and wife.”

Both couples raised strong-willed children. But in both cases, there was a clear demarcation between parent and child, and no question about the supremacy of love. Their love for each other came first. Any good that they had to offer, in their eyes, whether for their children or others, flowed from that.

My parents connection to the Reagan’s was well established by the time the young psychiatrist, Gary Gottlieb, evaluated my father that Thursday morning. During his campaign for a second term as President in 1984, to my distress, my parents taped a color picture of Ron and Nancy to the front window of our home to proclaim their support for the “First Couple”.

Years later, the experience that Nancy Reagan and my mother shared, as a spouse who was the primary caregiver of an Alzheimer’s patient, was one that is at once indescribable, and at the same time ubiquitous today throughout human societies. As my parent’s child, quite independent of politics, it is easy for me to identify with the heavy burden as described in the final days by the Reagan’s daughter Patty.

She wrote: “My father is dying. Only a few days left now. Maybe a week. Maybe his soul is already gone. It looks like that—blue chalk eyes, more like a child’s drawing than real eyes. No life in them, just existence.

It’s been 10 years since the diagnosis. Alzheimer’s. A disease that arrives with death as its soulmate. I thought I was prepared. So many waves of grief have crashed over me during these years. But now I think there is another diving-down place that’s still waiting for me. Two days ago my father’s eyes stopped opening at all, his hand is as pale as the blanket covering him and sometimes his breath just stops as seconds pass by and I wonder and hold my own breath. My father is dying and it feels like I’ve never thought about it before. Even though I’ve been living with the thought for a decade.

My father’s voice fell silent weeks ago. Until then the sound of his voice hummed through the room sometimes—not with words, but maybe they were words to him. I said to my mother, maybe he’s getting us used to the silence. She lives with all that silence, with the ticking by of minutes and the knowledge that death has to be better than ragged breathing and chalk blue eyes.

Her husband is dying. The man she loved for 52 years. Here is a snapshot of the waiting: A daughter holding her mother while she weeps, tears staining skin, a body shaking with so much pain you think if you were at the center of the earth you could probably feel it. My mother is tiny, her weight against me light, the back of her head is cupped in my hand. But her grief is huge and so heavy it pulls on the joints of my body. It will be okay, I tell her. But I have no idea if it will be.”

Had my father publicly disclosed his disease, at the time of diagnosis, I am sure he would have included a paragraph that mirrored Ronald Reagan’s open letter to America.(76) It read, “Unfortunately, as Alzheimer’s Disease progresses, the family often bears a heavy burden. I only wish there was some way I could spare Nancy from this painful experience. When the time comes, I am confident that, with your help, she will face it with faith and courage.”

As with my father, Reagan’s love for his wife was paramount. He stated it succinctly at the dedication of his Presidential Library, “Put simply, my life really began when I met her and has been rich and full ever since.” As with my father, after his diagnosis, life, ever so slowly, slipped away. Reagan’s last visit to his California ranch for a ride in his open Jeep with the vanity license plate, GIPPER, came in August, 1995. At around this time, the former First Lady commented that “It’s very lonely. Not being able to share memories is an awful thing. There really isn’t much you can do… and that’s the frustrating part of it. You know it isn’t going to get better, there’s only one way it can go. So you have to recognize that, and it’s very hard to watch.” Certainly my mother would agree.

Ronald Reagan died a peaceful death on June 15, 2004. Some time later, Nancy commented, “If a death can be peaceful and lovely, that one was. And when it came down to what we knew was the end, and I was on one side of the bed with Ron, and Patty was on the other side, and Ronnie all of a sudden turned his head and looked at me and opened his eyes and just looked … Well, what a gift he gave me at that point… I learned a lot from Ronnie, while he was sick – a lot. I learned patience. I learned how to accept something that was given to you, and how to die.”

My mother’s experience was different. She was not at my father’s side. She was not there to accept one last loving gaze, one final silent message of thanks and gratitude. My father died on September 15, 1998, under the loving care of my older brother, Bill, his wife, Kathy, and their family. My father no doubt felt my mother’s absence, as he continuously wondered aloud, “Where’s Grace?” But she was gone. On the morning she died, on December 9, 1995, she dressed and prepared my father for his ride to the Alzheimer Day Center. Once safely on his way, with the company of my sister, Kathy, a nurse, who by chance was visiting them at the time, she lay down on their couch and quietly and unceremoniously died, the victim of ovarian cancer whose diagnosis had been tragically delayed by inattention to herself while she labored in the service of her husband.

Tags: alzheimer's > caregivers > Family Caregivers > nancy reagan > Ronald Reagan

How Do We Compare To Ourselves in Health Care?

Posted on | March 3, 2016 | Comments Off on How Do We Compare To Ourselves in Health Care?

David Blumenthal M. D. of the Commonwealth Fund did a little comparison shopping in a JAMA article on Health Care Reform. But instead of simply comparing our system to those in Europe, he compared us to ourselves.

Here’s what he had to say:

“Given some Americans’ skepticism of foreign experience, home-grown examples may be more compelling. The Commonwealth Fund State Scorecard3 suggests that (1) if US health spending per person averaged the same nationally as among the 5 lowest-cost states (Utah, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, and Nevada), an estimated $535 billion (approximately 20%) less would have been spent on personal health services in 2014; (2) if rates of health insurance coverage averaged the same nationally as among the 5 areas with the highest rates (Massachusetts; Vermont; Hawaii; Washington, DC; and Iowa), an estimated 20 million more Americans would have been insured in 2014; and (3) if the national levels of mortality amenable to health care averaged the same as among the 5 states with the lowest rates (Minnesota, Vermont, New Hampshire, Utah, and Colorado), an estimated 77 000 fewer deaths would have occurred in 2014.

The country is large and diverse, and cross-regional comparisons may overlook limits on what any 1 place can achieve. However, such benchmarking strongly suggests that major gains in US health system performance are possible and could yield huge benefits for the American people.”

Virginia Tech Engineering Students Live Their Professional Ethics

Posted on | February 29, 2016 | 2 Comments

Source: VA Tech student

Mike Magee

Attention all health professional students! I would like to introduce you to 3 friends of mine. Well, to be accurate, they are not really friends, in fact I have never met them in person. Nonetheless, I greatly admire them, and am anxious for you to know their names.

They are William Rhoads, Rebekah Martin, and Siddhartha Roy. You may not know them, but they are at least aware of you. They recently wrote: “Engineers don’t take oaths similar to medical doctors’ Hippocratic Oath, but maybe we should. As a start, we have all made personal and professional pledges that include the first Canon of Civil Engineering: to uphold the health and well-being of the public above all else. In doing so, we affirm Virginia Tech’s motto, ‘Ut prosim,’ which means, ‘That I may serve.’”

The three are engineering doctoral students of Virginia Tech professor, Dr. Marc Edwards. In April, Dr. Edwards was contacted out of the blue by Lee Anne Walters, a Flint, Michigan mother of a lead-poisoned child. By then, Ms. Walters, had been betrayed by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), who would subsequently be proven to have “violated federal regulations”. Once obstructed, Ms. Walters sent tap water samples from her home to EPA Region 5 employee, Miguel Del Toral, who then collaborated with Dr. Edwards, and discovered that the tap water contained 2,000 parts per billion of lead, 130 times the allowable level.

When they sent the findings back to the MDEQ, they encountered a wholesale cover-up, and no corrective action. By then, the MDEQ was fully aware of the cause of the environmental disaster – a cost-saving 2014 action which switched the city from treated Detroit water to untreated Flint River water whose corrosive chemicals were leaching lead from ancient water pipes into the drinking water.

What to do? Edwards and his students discussed it, not just as a scientific challenge, but as an ethical dilemma. In the face of no committed resources, no geographic legitimacy, and active obstruction from the regional governmental body, there was more than enough reason to drop the issue. After all, here they were, on a campus in Virginia, 500 miles southeast of Flint. But that’s not what happened.

Instead, Dr. Edward, encouraged by his students, which now included two dozen volunteers, went “all in”. Edwards halted other funded research, and shifted $150,000 to the effort. Their first step was to mail out 300 sampling kits to Flint volunteers, who subsequently gathered 861 water samples over a single month.(MDEQ had run only 7 tests in the prior 6 months). The sample collection was subjected to very rigorous tracking and management since the students knew the validity of results would be challenged by the MDEQ

Next, The Virginia Tech students made several visits to Flint, meeting with residents, involving them in advocacy planning, and establishing trust which had long since disappeared. When requests for records went unanswered, the students demanded the files under the Freedom of Information Act, and uncovered proof that the MDEQ had misinformed the EPA that there was a corrosive control program in place, and had illegally discarded customer samples. Finally, the group teamed up with Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha at Hurley Medical Center and collected and released results of the blood lead levels of Flint children.

These final actions tripped a state of emergency, a switch back to Detroit water and direct involvement of the Obama Administration. MDEQ received a blistering review by Virginia Tech professor, Yanna Lambrinidou, who wrote that they were “understaffed, underfunded, lack knowledge and experience.” The students could have easily left it there, a isolated case of the bad guys brought to justice. But they and their Research professor sponsor knew instinctively that this was not the case. Rather, they examined the structural deficits that allowed this to happen:

- 150,000 different public water utilities in the U.S., with highly variable standards of excellence in examining the nation’s water for more than 80 contaminants.

- High degrees of unreliable reporting up though the vertical system of control – from local, to regional EPA, to national EPA.

- Highly variable levels of skill and engineering expertise within local water management offices.

- An EPA that is under-resourced in personnel and funding.

As impressive are the professional insights William, and Rebekah and Siddhartha have drawn from their unique educational mission.

“We are worried that a reward structure has developed that supports mainly self-promotion and dissuades the altruistic motives to do science for the public good that attracted many of us to the profession in the first place.”

“Our experience in Flint has shown us some unpleasant costs of doing good science. It can mean burning bridges to potential funding, and damage to your name and professional reputation. There also are emotional costs associated with distinguishing right from wrong in moral and ethical gray areas, and personal costs when you begin to question yourself, your motives and your ability to make a difference.”

Each and every health professional student could do well to emulate these three, and their fellow students, who went “all in” in serving the “first Canon of Civil Engineering: to uphold the health and well-being of the public above all else.” And for your teachers, many of whom have become entangled in the “Medical-Industrial Complex”, would each of them stand tall if faced with a similar call to action?

Tags: CDC > engineering canon > flint > flint water crisis > medical ethics > virginia tech

AMA’s New Sunbeam Crisis: The AMA Federation’s “Trojan Horse”

Posted on | February 25, 2016 | 3 Comments

Source:Wikipedia

Mike Magee

In August, 1997, the leadership of the AMA ignited an existential crisis by agreeing to loan their imprimatur to the Sunbeam corporation. The imprimatur, along with an AMA endorsement, was to be assigned to Sunbeam products in nine home-care categories including heating pads, vaporizers and blood pressure cuffs. In return, the Florida based company, led by the notoriously aggressive Al Dunlap, was to provide millions in royalties.

As soon as the deal was announced, all hell broke lose. Consumer advocates, legislators, and AMA members openly criticized the deal. Within a week, there was a highly critical New York Times editorial. That was enough for the AMA Board to intervene, launch an independent internal investigation, fire their executive vice president and four other staffers, and ultimately settle with Sunbeam for breaking the contract at the cost of $10 million dollars.

That is how seriously the AMA took the integrity of their imprimatur. All the more surprising then, that they have allowed pharmaceutical manufacturers to access the power and might of that very same imprimatur through their own organizational back door. The “trojan horse” that has facilitated entry is none other than the AMA Federation’s vaulted specialty societies.

The AMA’s unwillingness or inability to provide strict quality control over its now 121 specialty societies was revealed as a result of the publicity surrounding Nobel Prize economist Angus Deaton’s finding that the survival curve in middle aged, white American males had curved downward over the past decade as a result of prescription opioid abuse, most especially of OxyContin.

OxyContin is produced by Purdue Pharma, a one drug firm begun as Purdue Frederick Co. in 1952 by Academic Medicine’s favorite philanthropist, Arthur M. Sackler, MD. Sackler was the father of modern pharmaceutical marketing, whose feats were well catalogued in the biography accompanying his posthumous induction into the Medical Marketing Hall of Fame in 1997.

Sackler’s game book was remarkably consistent over the years. By following these five steps, he became one of the lead designers of the modern Medical-Industrial Complex.

Step 1. Create a quasi-medical organization for legitimacy.

Step 2. Provide funding to the organization to sponsor quasi-academic vehicles (journals and CME programs) to publish supportive articles, and then re-educate practitioners toward the medicalization of your target condition and the need for treatment of this condition with your therapy.

Step 3. Expand the number of professional and consumer organizations to create momentum, demand, and implied consensus.

Step 4. Integrate these programs with mainstream intelligentsia by ample funding in high end medical journals and generous philanthropic support of brand institutions, so that by simple name association, you reinforce your own brand’s integrity.

Step 5. When over-prescribing ignites a backlash, generously and magnanimously participate in the corrective steps, which you yourself made necessary.

Exactly how and when the Purdue Pharma “trojan horse” penetrated the venerable AMA Federation has been well documented in prior publications. What is abundantly clear is that the area of pain management is clearly over-represented and ethically compromised within the AMA Federation. Beyond the historic societies that cover psychiatry, neurology, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and oncology (all of whom have strands devoted to pain management), there are also The American Academy of Pain Medicine (1983), The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (1988), the American Society of Addiction Medicine (1988), and The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (1998).

The prior series, the Man-made Opioid Epidemic, documented the fundamental absence of any meaningful quality control checks on the AMA’s own Federation members. In a recent AMA blog post, AMA Presidency Steven J. Stack, M.D., writes, “We have a defining moment before us—the kind of moment that we will look back on in years to come as one in which we as a profession rose to the challenge to save our patients, our families and our communities during a time of crisis.”

He then encourages physician members to cooperate with prescription drug monitoring programs and improve their education of how best to approach opioid prescribing. Where should they turn for such education? Stack suggests, “The AMA has gathered more than 100 state and specialty-specific education resources in a one-stop shop for the best and most up-to-date education that organized medicine has to offer. Be sure to take advantage of these materials.”

These include the very same Sackler-infused, Purdue-dominated, OxyContin-fueled characters who ignited this whole mess to begin with. These are the inventors of “pain – the 5th vital sign”, the marketers disguised as CME providers, the malleable state medical board leaders, the patent holders of delayed release technology which they assured rendered OxyContin “addiction proof”.

What then should President Stack and the AMA Board of Trustees do instead? As with the Sunbeam crisis, they should fund an immediate, thorough, internal investigation directed at their own management standards and the ethical integrity of their state and specialty societies. Individuals and associations found to be directly responsible for this modern day Sunbeam crisis should be permanently severed from the organization.

The AMA has a systemic problem that requires immediate attention. If left unaddressed, it poses a much greater risk to the organization than Sunbeam ever did. Questions that the AMA Board of Trustees need to address include:

1. As with 501C3’s, should each national member be required to submit a full financial report, including educational offerings, and complete list of sponsors each year?

2. Should leadership of participating member organizations be required to complete and sign-off on a conflict of interest online program each year to maintain membership?

3. Should Federation member websites be required to include a “sponsor” heading in their navigation bar displaying a complete list of commercial sponsors/advertisers which provided financial/in-kind support for operations, CME funding, public affairs funding, and/or journal advertisements, for the past 5 years, including donations to the member organization and any associated Foundations?

4. Should the results of that annual declaration be available on the AMA public website?

5. Has the AMA ever decertified a Federation National Medical Society? Which, when, and why?

6. Should the AMA establish formal Quality Assessment of their Federation members focused not on membership, but on educational, financial, and ethical performance?

Tags: ama > AMA Board of Trustees > AMA Federation > AMA specialty societies > american medical association > Arthur M. Sackler > medical ethics > oxycontin > purdue pharma > Steven J. Stack

Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Posted on | February 12, 2016 | Comments Off on Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Mike Magee

My father was one of the 45,000 military doctors to serve in WW II. He entered active duty after his internship in late 1943. By March, 1944, he found himself in Texas receiving special training in Psychiatry. Six months later he would be awarded a Bronze star for his service as an emergency commander of a neuropsychiatric hospital in a war zone in Southern France. Since America’s entry into the war, the Army had attempted to pre-identify and reject any candidates who might be pre-disposed to becoming psychiatric casualties under fire. Military leaders believed selection had been too liberal in WW I, and that this had resulted in high levels of psychiatric distress on the battlefield. By the time my father entered the European war theater, some 2 million draftees or 12% of those examined had been rejected using the military’s new stricter selection criteria. Of the 5 million rejected on medical grounds, nearly 40% were labelled “neuropsychiatric”.

All of this would have been fine with Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, if it had worked. But in the first major test, America’s invasion of French North Africa in Tunisia, American psychiatric casualties were occurring at double the rate seen in World War I. A startling 34% of all battle casualties were labelled neuropsychiatric. Based on the military criteria and rules validated by the new Army Chief of Psychiatry William Menninger, a psychiatric label on the battlefield earned you a one way ticket home. Marshall had had enough. He abolished the screening, and re-enlisted a majority of the men that had been rejected on neuropsychiatric grounds. A later study found that 82% of these former rejectees performed successfully as soldiers.

With involvement in selection gone, Menninger and his Psychiatric colleagues concentrated on battlefield management of what had been loosely labelled “shell shock”. Since World War I there had been disagreement whether the constellation of symptoms that had appeared in 15% of the soldiers was a physiologic condition or some kind of psychological problem. The symptoms included everything from stuttering and crying to deafness and blindness, from hallucinations and amnesia to chest pain and inability to breath. Fundamentally, these soldiers were out of commission, at least for a period of time.

The approach settled on in WW I involved intervention as early as possible and as close to the point of injury as could safely be accomplished. This meant putting psychiatric support into the field and positioning it close to the action. Affected soldiers were initially treated with rest, sedation and warm food. This was reinforced with optimism, persuasion and suggestion. The condition the soldiers were told was “normal” and not their fault. They would get better. Military medical leaders then believed this first step could successfully put about 65% of the soldiers back on the front within 4 or 5 days. If not, the soldiers were shipped to facilities some 15 miles from the front and treated “more aggressively”. If that didn’t work, they went to base hospitals 50 miles from the action and spent 3 months in recovery. If that failed, then, and only then, would they be shipped home.

Marshall liked this approach, especially the part about not linking the condition to an automatic and immediate ticket home. The experience in Tunisia had shown that the more inexperienced the Medical Corps team was, the quicker casualties would be labeled “neuropsychiatric” and shipped out. At Marshall’s request, Menninger came up with a plan. This largely adopted the WW I approach, reinforced by the use of barbiturates and ether anesthesia if necessary for initial sedation of hysterical soldiers. In the most severe cases, other experimental treatments would be utilized like intravenous sodium pentothal, the “truth serum”, to draw out (and hopefully discard) the troubling traumatic memories of war. The echelon system would provide progressive evacuation of more serious cases and echelon 3 would be reinforced with special neuropsychiatric and convalescent hospitals where possible. All this sounded great, except for one thing. There were not nearly enough psychiatrists to execute the plan. So Menninger came up with the idea to train all medical officers in what he called “forward psychiatry”.

To do this he developed a diagnostic manual – Medical 203 (which after the war would become the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM). This was a structured approach to diagnosis and treatment, including the use of barbiturates, and a series of training films which included professional actors to illustrate what the medical officers might encounter. The fictional major in the film not so subtly reinforced that psychiatric treatment was a fundamental responsibility of all medical officers. The soldiers that were being treated were not abnormal people in normal time, but rather normal people trapped in an abnormal time. Every man has his breaking point was the message. These men were not “shell shocked”, they were suffering “battle fatigue”.

My father, in March, 1944 received the new training with other medical officers. He viewed the War Department Official training Film 1197. It had been produced on October 20, 1943 and titled: Early Recognition and Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Conditions In The Combat Zone.

The film began with a static slide that read:

““Any medical officer may be called upon to treat neuropsychiatric casualties. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists, the burden of early recognition and treatment of these casualties will fall on medical officers without special training. The attention of all medical officers , therefore, is invited to their responsibility for the mental as well as the physical health of military personnel.”

Early in the film, Menninger surfaced all the major objections doctors like my father might have by having the “Medical Officers” in the film raise questions with the “Major”. After a brief opening film segment showing an hysterical fictional patient with battlefield exhaustion, the major invites comments. Officers objections: 1) “I don’t see what else the officer (in the film) could have done. There doesn’t seem much point in keeping a patient like that on the battlefield”. 2) “Major, we’re going to be busy out there with patients who are really shot up and we won’t have time to monkey around with guys like that.” 3) “Major, I’m a surgeon. Looks to me like this is a job for psychiatrists.” 4) “That soldier must have been a misfit from the start to break down like that.”

The major’s response sets the record straight in pretty clear terms: “Gentlemen, you are not requested to treat these patients. You are directed to do so. May I acquaint you with a few statistics from recent campaigns. The size of the problem will startle you. These figures from Italy seem to indicate that 20% of all the non-fatal battle casualties were not wounded. They were suffering from neurosis. In Sicily the overall figure for the entire campaign was 14.9%. When you add up the easy and the hard days of the Tunisian campaign, you will find that 16% of all the non-fatal casualties were suffering from neurosis. In prolonged engagements where the going is really tough, we find that 30% to 50% of all men coming under your care in the divisional area are suffering from combat exhaustion…That means that 1 out of 3, or even 1 out of 2 soldiers coming under medical canvas does not have one drop of blood on him…..You are the members of the Medical Department and to you are entrusted the care of all of the sick. There are no specialists on the battlefield. If you say you are a surgeon and can only handle the surgically impaired, you have failed in your mission. Out in the mud, you’ve got to be a medical soldier and meet all comers.”

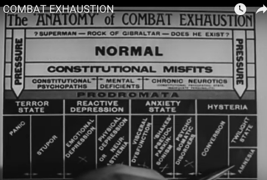

Now that he had my father’s and the others attention, they got down to business. A diagnostic tree with 4 conditions including hysteria, anxiety state, reactive depression, and terror state. Cutting across these four categories are the soldiers themselves who vary from being “Superman – Rock of Gibraltar” to “NORMAL” to “Constitutional Misfits.” The message is, “You will be dealing with all comers, and they will vary widely, but they all need your help.”

Then seamlessly, the major moves on: “…let us review some of the drugs available to us in narcosis therapy and chemical hypnosis available in your #2 Chest..”

1) Sodium Amytal: 9 to 12 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep) …wake, feed, bathroom…re-treat for total 24 hours. Also available IV (5 to 8 cc) (EI Lilly)

2) Nembutol: 4.5 to 6 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep)…in combat zones, massive doses are needed in treatment.

3) Phenobarbital: 4.5 to 6 grains (10 to 12 hours sleep)

4) Sodium bromide: dose and effect highly variable. Can be toxic. Used only if nothing else is available.

5) Pentothal IV: Short acting “truth serum” to surface suppressed memories.

6) Ether: Can be used to get unruly patients under control.

And in conclusion the Major delivers a clear instruction that would be actively followed by doctors in war zones, and become embedded in the practice of medicine for the next half century, “You have the facility of sedation and reassurance. Use them.”

At the end of the war, the doctors returned home with a distinct bias toward specialization and pharmacologic intervention – name it, treat it, cure it. Medical 203 morphed into DSM. By 1970, with the Medical-Industrial Complex now near fully funded by government research dollars, one in seven American adults, bruised by the Cold War, were on tranquilizers.

Tags: battlefield exhaustion > DSM > medical 203 > Military Medicien > overuse of psychiatric medicines > selective service WW II > shell shock > william menninger > WW II